Rodgers, Barca and 'Tiki Taka'

Football coach and blogger Jed Davies examines the 'Tiki-Taka' philosophy deployed by Barcelona under Pep Guardiola and Swansea under Brendan Rodgers.

The following piece gives an insight into the tactical approach that helped earn new Liverpool manager Brendan Rodgers a reputation as one of the finest young coaches in the game...

The 'long ball' tactic was first conceived in the 1950s by theorist Charles Reep in England. Reep was a football enthusiast and analyst who studied in great lengths the number of passes that led to a goal and what positions the key passes took place.

The 'long ball' tactic was commended and celebrated by Charles Hughes who stood as head of coaching for the English FA during the 1990s. Hughes saw success in Reep's analysis and based much of his ideologies around Reep's principles:

- The three pass optimisation rule: statistics showed that between three and five passes were evident before the majority of goals scored since the 1954 World Cup;

- Nine shots per goal: the average number of shots needed per goal for each team;

- Goals scored 12.3 yards from goal: the mean from which goals were scored;

- Optimum position for an assist: between the corner flag and six yard box.

The result of these findings have laid the foundations to English football for generations and the offside rule changes did not alter the findings significantly. British football has since built teams around:

- Fast wingers who are capable of finding the space in the 'optimum position for an assist';

- Forwards with good aerial ability to provide the knock down and squeeze the passing in the final third as often as possible;

- An approach to tactics that has meant the ball is in the box as often as possible so that goals can be scored from the suggested distance from goal;

- An approach that led to chance creation as often as possible to score goals.

The product of this is the 4-4-2 system or any variation of this (4-2-4 etc) that requires wide wing play and balls being played over the midfield to the striker to knock the ball down to the midfield in a more advanced position on the field. This formation would eventually lead to the defensive minded players playing midfield to be exceptionally good at winning the ball back and playing a short pass into a player who could then start the route one style of football: the 'Dunga/Makelele role'.

The long ball system makes sense and requires a set of very particular players to fit the perfect mould for each role. The system is perhaps far more successful over the course of history compared to the 'total football' of Holland's 1980s team or the fluent passing Brazil of 1970, Argentina of 2006 etc.

Football evolves over time. The requirements of a modern day football are in stark contrast with those of the 1950s and 60s. Players are now expected to run much further than before, the ball is now lighter and can be manipulated in ways it simply could not before.

Spain won the European Cup in 2008 and World Cup in 2010 without players that fit the 'long ball' mould. They won the tournaments playing 'Tiki-Taka' football, a type of football that has found its roots in Holland's 'total football', but this time instead of a system that allowed players to interchange positions fluently it turned its focus on the fluency of possession and the very importance of it. This approach aimed to control both the ball and the opposition.

Brendan Rodgers of Swansea FC swears by 'Tiki-Taka' football and the recent all round appreciation for the way that Swansea play football has become of significant interest:

"I like to control games. I like to be responsible for our own destiny. If you are better than your opponent with the ball you have a 79 per cent chance of winning the game - for me it is quite logical. It doesn't matter how big or small you are, if you don't have the ball you can't score.

"My template for everything is organisation. With the ball you have to know the movement patterns, the rotation, the fluidity and positioning of the team. Then there's our defensive organisation...so if it is not going well we have a default mechanism which makes us hard to beat and we can pass our way into the game again. Rest with the ball. Then we'll build again." (Rodgers 2012)

The 'Tiki-Taka' approach still does, however, require a whole new set of fundamentals to be in place in order to work. Players need to trust their teammates to do the right thing when they are on the ball and the success of the formation relies on every player to be doing their set of jobs in the correct way. The approach works on the principles that 'the whole is greater than the sum of its parts':

"The strength of us is the team. Leo Messi has made it very difficult for players who think they are good players. He's a real team player. He is ultimately the best player in the world and may go on to become the best ever. But he's also a team player. If you have someone like Messi doing it then I'm sure my friend Nathan Dyer can do it. It is an easy sell." (Rodgers 2012)

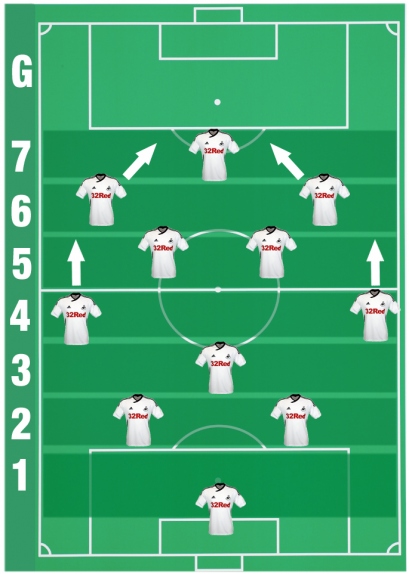

Brendan Rodgers recently sketched out his formation and explained his approach to the game for journalist Duncan White. First, he divides the pitch into eight zones and then plots out his formation. The division of zones is suggestive that each player when in possession should play a particular role, including the goalkeeper and two centre-backs:

"When we have the football everybody's a player. The difference with us is that when we have the ball we play with 11 men, other teams play with 10 and a goalkeeper." (Rodgers 2012)

The formation is nothing new; however, it's the way in which each player is used within the formation that allows the approach to work. Therefore an adjustment must be made in the traditional view of this formation from a 4-5-1/4-3-3/3-4-3 to a 1-4-5-1, 1-4-3-3, 1-3-4-3 or even a 1-2-6-1. The point here is that the formation has lost its simplicity of which it can be viewed. The formation is now one not viewed as defence, midfield and attack but instead, over seven zones of the pitch. Barcelona use a similar system: many noted their recent change in formation from a 4-3-3 to a 3-4-3 with the introduction of Cesc Fabregas, but the truth is they have not really changed formation as much as many have been led to believe.

The centre-forward, creative inside wingers and attacking wing-backs have been consistent features of many formations throughout generations and their roles do not change with much significance. It is the role of zones 1, 2, 3 and 5 that act as the core to the build-up play and the success in retaining possession over the entire duration of the game.

- The goalkeeper is seen as the sweeper and has a set of similar roles (in possession) to zones 2 and 3. The 'keeper is expected to act as a pressure relief for under pressure teammates;

- Zone 2 consists of two centre-backs who, unlike in other formations, are expected to play a huge role in keeping possession. They also act as pressure relief to the midfield and an obvious option for the goalkeeper to play the ball out to. Instead of passing the ball 30, 40 or even 50 yards the majority of their passes will be kept under 10 yards;

- Zone 3 has arguably the most important role to play in keeping possession. This player must be particularly good at keeping possession under pressure from opponents and will often see their passes also being played short for the duration of the game. Leon Britton, Pirlo and Xavi are examples of players who act as the deep lying play makers, the water carriers, the short playing quarterback or the 'volante de salida' which simply translates in football terms as the outlet for under-pressure teammates. "I get the ball, I pass, I get the ball, I pass, I get the ball, I pass." (Xavier Hernandez 2011);

- Zone 5 have the role of consistently finding space acting as the final piece in the triangular connection between teammates. These two centre midfielders, like the player in zone 3, must have high standards of passing ability and awareness to keep possession but must also have high levels of stamina to work as box-to-box midfielders. They do not necessarily look to create the spectacular, but are the catalyst in the change of speed in which the possession play is being played at, the moments of which they choose to change speed and direction of the ball are key to the succession in creating opportunities to create an assist or goal. Both zones 3 and 5 will be expected to boast 90 per cent pass completion rates in order for the system to work successfully;

- Zone 4 are expected to act as support to players in possession and are too expected to look to work themselves into the triangular connections made with teammates. They are expected to get forward as play moves up the pitch and follow the ball back when play dictates so. Zone 4 will opt to cross the ball from the opponents' byline rather than from deep, in keeping with the 1950s optimum assist zone in zone G;

- Zone 6 will consist of arguably the most creative players on the ball either in the sense of dribbling ability or of passing ability to create. Messi, Scott Sinclair, Nathan Dyer, Pedro, Afellay, Cuenca et al are examples of players who play in this system and portray the qualities expected. This zone will also be responsible for much of the goalscoring as well as the assisting of goals;

- Zone 7 needs a player who is good technically and can hold the ball very well as well as link up the play. The difference here to the traditional long ball target man is that the lay off will usually be followed with this player spinning away to find space and having full awareness of where space is around him in all areas of the field, the 360 degrees of vision with and without the ball;

- Zone G is the zone to which optimum chance creation occurs. However, the difference in this system is not that of desperation to play the ball as you get into this zone, but to see if the opportunity is indeed available. If not, then the only viable option is to turn and play the ball back which then may well get played all the way across to the other side of zone G, or even back to the same side if the opponents' defensive positioning has changed. Patience is the key here and the general rule that one goal is scored to every nine shots will alter due to the quality of opportunity created being significantly better;

- Lastly, it is important to remember that 'the whole is greater than the sum of its components' and the entire team, despite set into separate divisions of the field, is expected to work together; to move up together and backwards together, much like the waves of the ocean crashing onto the surface of the beaches.

As mentioned before, absolute belief that each player will do the right thing is vital - therefore meaning players will not wait and watch their pass reach a teammate's feet, but pass and look for space for yourself, trusting not just your teammates but your own ability to pass and that it will reach the teammate you aimed for.

The ideal is that every player will have constant awareness of every other teammate's positioning and offer themself as a passing option whenever possible as many times as possible. As a general rule, players should look up around every 5-10 seconds to give themselves three options before they get the ball, this way the players are never caught out in possession. Expect the ball at any given moment.

Barcelona play with a higher tempo without the ball, pressurising the opponents high up the field:

"You win the ball back when there are 30 metres to their goal, not 80." (Guardiola 2009)

Therefore, all players are expected to defend from the front and learn to keep men behind the ball as much as possible. This approach also allows the 'keeper to act as a sweeper when the opposition attempts to play high balls over the high back line. A contrast in the older approach that defensive players do their duty and the attack wait to counter when their teammates win the ball back.

The alternative to high pressure, if the players you have struggle with fitness, is the complete opposite. To site back and tackle only in your own half and invite the opponents to try and play their way through you. Taking inspiration from basketball's approach of dropping back and protecting 'the key'. This will encourage the opponents to either play long ball and give the ball back more often than not or encourage the opponents' defence to become play makers. They are often not the best passers and this will lead to mistakes being made. It is important, however, not to get carried away with the counter attacking approach after winning the ball back in deeper positions. Patience and the changes in tempo are key.

Applying to youth football teams

Total knowledge and understanding are a good place to start alongside the ability to keep the ball for youth football in the UK. Many children are playing in teams not quite understanding their roles throughout the UK.

An important factor of successful creativity and development is not to punish mistakes, but reward successes. When one is punished for attempting to create, they will refrain from successfully creating in the future because they fear failure. Many coaches in youth football today are killing creativity and taking the good out of the naivety of the youth.

A handbook should be given to each player not only explaining the roles of their own position but the roles of all other positions to get the full concept of Tiki-Taka football.

"My template for everything is organisation. With the ball you have to know the movement patterns, the rotation, the fluidity and positioning of the team." (Rodgers 2012)

Identifying your own youth players' skills and potential is key in the selection of roles within the zones when in possession of the ball.

Practice will make perfect. Perfect football is achievable.

Maybe one day Sunday league football will be enjoyable to play in for every position on the field. We might fail at first, but progress is made through failure.

Progress will be made.

Set pieces

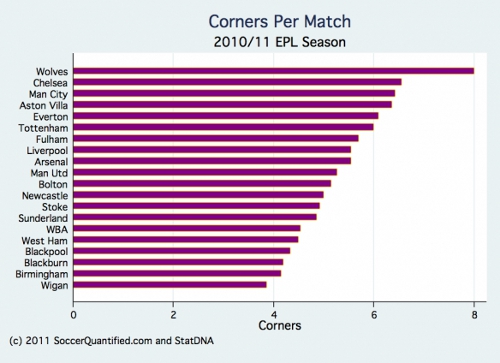

"Here are the overall numbers of corners per team in this sample of matches. On average, teams took 5.35 corners per match. This is consistent with the five-year league average of 5.52. While Wolves were particularly high at around eight in this sample (for the season as a whole this year, they are at 6.2 - also quite high), the rest of the teams ranged between a low of about four (Wigan) and six (Chelsea), with the better performing teams this year producing more corners.

(from 10/11 season data, http://www.soccerbythenumbers.com/2011/05/why-goal-value-of-corners-is-almost.html)

While this is not what we're primarily interested in, it gives us a baseline against which we can compare the shot and goal production from corners. So here is the answer to question one: what are the proportions of corners actually producing shots on goal, according to the StatDNA data?

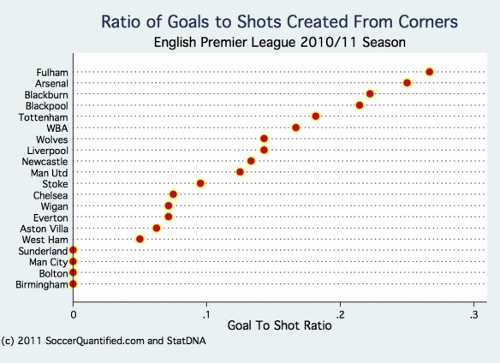

The data show that, on average, about 20.5 per cent of all corners (that's one in five) led to a shot by the team that took the corner within three touches of the ball. There also is considerable variation across clubs on this. At the low end, some of the very best clubs in the league managed relatively few shots - about one to 1.5 in 10 - relative to the number of corners they produced. In contrast, some of the worst teams in the league produced a relatively high number of shots in the aftermath of corners (Chelsea is the exception), at a rate of one in four or even one in three (West Ham and Stoke).

But clearly, there is some slippage. Another way to think about this is that most corners did not yield shots (about 80 per cent of them don't). Think about how different this is likely to be from free-kicks. But on to question two. Of the corners that actually led to shots within three touches, what were the odds that the ball crossed the line? Take a look:

There is even greater slippage when it comes to turning shots into goals than turning corners into shots. In fact, it's almost twice as much. On average, about 11 per cent or one in nine shots created from corners produce goals. Incidentally, that's also right around the average ratio for goals to all shots taken in soccer matches (the Reep ratio). In this sample of matches, Fulham and Arsenal led the league in converting corner-created shots into goals at a rate of over .25, while at the low end, none of the shots created by Sunderland, Man City, Bolton or Birmingham found the net.

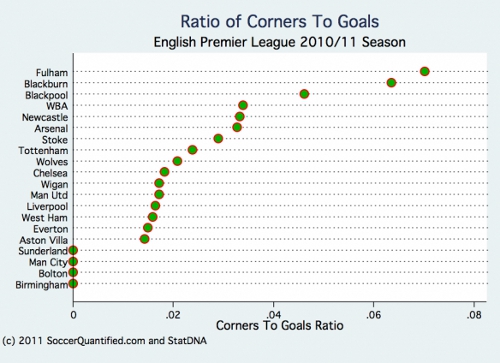

So what do the patterns look like when we put all this together? The graph below of the ratio of corners to goals tells the combined story.

The yield from corners ranges from zero to .07. On average, the data show that a corner is good for (drumroll ....) 0.022 goals. This means that the average EPL team scores one goal from a corner about every 10 games. And this helps to explain the lack of a correlation between the number of corners and goal scoring. The infrequency of the goals from corners suggests that, well, corners are useless when it comes to scoring goals."

(http://www.soccerbythenumbers.com/2011/05/why-goal-value-of-corners-is-almost.html))

Conclusion

From the data above it has become increasingly clear that at top level football, where defences are well organised, set pieces are a case of improbable chance more often than not. A corner is no longer a regular goal scoring opportunity in reality; therefore, as an alternative approach, perhaps a corner should be thought of as opportunities to maintain possession in the final third of the pitch, or if you are the defending side, the opportunity to counter attack.

Obviously, if you have a team of giants (Norway/Denmark in previous years) with the combination of an excellent corner taker - which is rarely found even in professional football - then a corner is by all means a real goalscoring opportunity.

As a regular Cardiff City match attendee I can safely say I have only witnessed a handful of goals scored from corners over the last five years, despite possessing Peter Wittingham, a player considered to have the best technique outside of the Premier League, and players such as Roger Johnson, Jay Bothroyd, Mark Hudson, Ben Turner amongst others who are all proven threats in the air. Cardiff have found far more success from indirect free-kicks and long throw-ins over the last five years.

So perhaps a corner needs to be reconsidered entirely and a short ball should be played, freeing up the 18-yard box and starting the attack again rather than launching the ball into their goalkeeper's hands and allowing the opponents to break.

The implications of this would by and large be huge. With only a handful of players either standing in or around the opponents' area, a corner would no longer become the opportunity for hectic movement inside the box, but an opportunity to re-start in an opponents' half with players tactically scattered over the final third. The opportunity to make and create space to then play the chance creation ball in a moment of chance creation opportunity would be asking a different set of questions to your opponents. Perhaps less is more in this sense.

This guide does not suggest that this is the best approach by any means, but questions a part of the game that most professionals at the top end of the game right through to Sunday league footballers take as a given. "We've won a corner, now send all the big lads forward." Maybe the complete alternative is better?

There is, however, something about scoring a last-minute equaliser from a corner against a team who have outplayed you from start to finish (see Ben Turner's last-minute equaliser against all odds Cardiff City v Liverpool Caring Cup final 2012), but perhaps that's all it should be, a desperate chance against a team who you cannot outplay another way.

It is worth noting that (from experience) in youth football and in the lower leagues, corners have a much higher success rate and quick counter attacking football from one end to the other does not happen so frequently.

Of course, there is no right and wrong in football, and this handbook should most certainly not be given as a blueprint for how to play. Tactics and football itself are always evolving - Barcelona have changed their set-up every year for the last three years despite being labelled as the best team in history.

Do you find a formation that fits the qualities of your players or ask your players to fit the mould of a style of play and play their part in doing so? As with most things football, the answer to this question is a highly subjective one. No one is saying that one method is more successful than another: from Stoke to Barcelona (albeit one club is clearly more successful here), it's all football. But, if I were to answer the question of what football is about for me, as a player, a coach or a fan, I know for certain which style of football I'd like to see being used.

However, the objective of the game is to win and with winning you'll find the secret to the enjoyment of the game. Just ask Greece of 2004 and Italy 2006 whether they'd swap those trophies for the trophy-less but praised history of the Netherlands.

This piece was originally published on www.thepathismadebywalking.wordpress.com.