Tomkins on the great Barnes

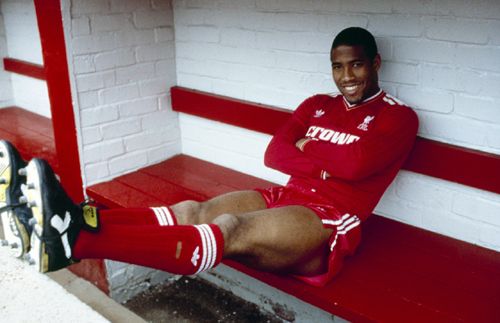

In an excerpt from a new eBook which aims to put together the best starting XI from Liverpool's rich history, columnist Paul Tomkins pays a glowing tribute to former Reds star John Barnes...

An outstretched left boot, planted on halfway-line chalk: a perfectly executed block-tackle. A spin into space, and half of the Anfield pitch opens up; new-boy John Barnes is away, running at the defence of table-toppers QPR. The ease with which, having approached the edge of the box, he jinks to his left, past a lunging tackle, transforms a great skill into something effortless.

But it is the way he drags the ball to his right, and somehow readjusts his balance, that defines one of the greatest goals the famous stadium has ever seen; it defies belief, not least because he somehow manages to accelerate in the process. England international Terry Fenwick is bypassed - a Tussauds waxwork in blue and white hoops.

England international full-back Paul Parker slides in, but is not quick enough. England international goalkeeper David Seaman - beaten by a Barnes curler into the top corner earlier in the half - is left helpless again, as the Reds' No.10, with right instep, nonchalantly slips the ball beneath the man in green.

John Barnes had impressed in the early part of his debut season, but this is the moment the Jamaican-born winger arrives. The Kop, who'd been deprived of the chance to see the new man due to a collapsed sewer that saw the stadium closed until mid-September, were finally getting to see his genius first-hand.

His home debut had been against Oxford United, and he scored a fine free-kick. The Reds then beat Charlton, Derby and Portsmouth at home - Kenny Dalglish's side scoring 11 goals in a trio of victories - although Barnes was not amongst the scorers. But then came that QPR game, and an idol was born. In his 1999 autobiography he noted that it was the most memorable moment of his Liverpool career.

For the next four years the new No.10 absolutely terrorised English defences, scoring 75 times in all competitions in the process. His versatility was showcased in the way he went on to excel at centre-forward in 1989-90 (having ended his time at Watford in the role), and when, after an Achilles tendon injury in 1991 sapped his acceleration, he later rebuilt his career as a deep-lying central midfielder, recycling possession and, at the age of 32, earning an England recall in that particular role.

It's fair to say that John Barnes was viewed with suspicion when, in June 1987, Dalglish signed the Watford winger for £900,000; a fairly hefty fee that was 60 per cent of the then British record (at a stage when Liverpool had never broken the £1million barrier - that happened a month later, with the procurement of Peter Beardsley).

There were no black players at Liverpool or Everton at the time, in an era where racism from the terraces was still rife. To make matters worse, Barnes' heart had been set on a move to Italy - at the time the leading league in world football. While Watford contacted Spurs, Liverpool and Manchester United, the player's agent, Atholl Still - a former opera singer - was hawking his client to leading Serie A clubs. It was widely known that a video had been produced to try and seduce AC Milan and Juventus, but only Sampdoria and Verona were interested.

A quote appeared in the Liverpool Echo saying that Barnes wanted to move abroad or stay in London, the latter being patently untrue. There were also doubts about a player moving from a long-ball, low-expectations side with no great top-flight history, and whether or not he could adapt to the pressure and style of play at Liverpool. Those fears, expressed far and wide, were shown to be truly and utterly misplaced.

Barnes was nothing short of sensational. Despite his solid frame (before it became more - how shall I put it? - meaty), he glided across the pitch, moving with grace and poise. And for a silky-skilled winger, he had end product.

He got into positions with pace, power and skill, and then found the killer pass or the inch-perfect cross (how many times did John Aldridge have to just nod in on the six-yard box, so delightful was the curve and weight on the centre?). In an era before assists were recorded, by viewing all the league goals from the late '80s and early '90s (courtesy of grainy videos located in the attic) it's clear that he never once failed to get into double figures in those first four campaigns.

Despite a full decade at Anfield, did Barnes ever perform better than in his first year? With those constant mazy dribbles, astute passes and 15 league goals. Or did the shock and awe of that first season create a fantasy, where anything less than beating several men and providing a cool finish, produced disappointment? Had he painted himself into a corner of perfection? Maybe it's an illusion, but by his second season he already seemed a fraction heavier, and only registered eight times in the top division.

But this bulk and strength, allied to pace and quick feet, made him a hugely effective centre-forward, and he featured there on occasions when he won his second Football Writers' Player Of The Year, after finishing the league's top scorer, with 22 goals, plus six more in the cups. Another fine goalscoring season followed, and in those first four years he was averaging over 15 a season.

That dropped to less than four a season for the next six years, to highlight how his game had altered. Still, in 10 straight seasons - with Watford and Liverpool, between 1981 and 1991 - he never registered fewer than 13 goals in a season, and for the Reds he managed 108 goals in 407 appearances. To put Barnes' scoring record into perspective, Ryan Giggs - another prodigious winger whose game was reinvented in a similar way, but who has spent his entire career at a dominant club - had scored 163 goals in 909 club games, as of the summer of 2012. By contrast, Barnes, in his 19-year career, scored 35 more in 128 fewer matches.

One hallmark of greatness is just how good the player was at his peak, just how brightly he burned. Another is the duration of his excellence, precisely how long the flame lasted, even if it wasn't quite as luminescent. Barnes had 10 years in Liverpool's first team, but it was those first four years that mark him out as a legend. The question for such players becomes whether or not their legacy is ruined by their merely human years.

Is that perfection blemished, or can you place those vintage years into a glass display cabinet, and label them untouchable? Had Barnes stayed as a struggling winger, short of the old pace, he may well have eroded some of those memories. The fact that he managed several more years in a completely different role probably helps, because he wasn't damaging the memory of Barnes the winger.

Perhaps the hardest question to answer is just how Barnes would be remembered had he arrived in 1994 as a portly possession master. Would people see a Xavi-esque ball retainer, whose appreciation of time, space and the weight of a pass, kept Liverpool ticking over with metronomic rhythm, or would he have been viewed as a lazy, tackle-dodging midfielder who failed to burst with dynamism into the box?

Perhaps it didn't help that he was partnered with Jamie Redknapp, who was brave in always wanting the ball, but like Barnes, not much good at fighting to win it. By the time Roy Evans plumped for midfield steel, it was Barnes, now almost 34, who made way for Paul Ince. If those first four seasons saw a '10 out of 10' player, he added six more as a seven or eight. Despite 224 games for the Reds after his Achilles dulled his verve, his legendary status was confirmed by the first 178.

To be recognised as greats, players are often expected to be part of a successful side, and there's no doubt that Barnes, at his best, fits the bill - because he elevated an excellent Liverpool side to a sensational one. His less remarkable incarnation was in keeping with the club as a whole - when his Achilles snapped in 1991, Liverpool's demise was hastened. Due to the post-Heysel ban, Barnes also missed out on appearing in the European Cup, which, through no fault of his own, left one major question unanswered. Most greats lit up that particular stage.

Having said that, he was the undoubted creative light in what Tom Finney described in 1988 as the best English side he'd ever seen, and it almost didn't need that highest-level participation. At the time, only AC Milan - whose first of three European Cups in six seasons was still a year away - looked capable of matching the Reds.

As an individual - albeit one finely attuned to the team's needs - Barnes had it all. He displayed skill without excess; flair without showboating. There were nutmegs and drag-backs aplenty, but perhaps as a result of Graham Taylor's hard-line Watford drilling - and the military discipline of his colonel father - the aim was always to be as direct as possible: get into the heart of the opposition box, or get to the byline to deliver a cross.

If space was tight, and there were three men around him, then the tricks might come out - but only to work himself free. Nothing was overdone or overblown. No blind alleys were wound down. Nothing was done to humiliate an opponent. He'd shift the ball one way, then the other, and the balance was perfect. The acceleration would do the rest.

Barnes was also excellent in the air. Every headed goal seemed to be met with the commentator noting "a rare headed goal by John Barnes", yet he got several each season. His upper body strength was immense, aided by the thighs of a bodybuilder. Matthew Le Tissier - himself no lightweight - once remarked that, in going shoulder to shoulder, he just bounced off Barnes. In his 1996 autobiography, Ian Rush describes Barnes thus:

"A beautifully balanced runner, who could glide past defenders seemingly effortlessly. He also had great vision and the ability to split defences with one telling pass [...] But his greatest asset of all - and one that a lot of spectators have never fully appreciated - has been his sheer physical strength. When he had the ball he could hold off two, or even three, defenders with his power. At his devastating best, Barnes was a player of true world class."

In 2006, Barnes was voted fifth in the official Liverpool website's '100 Players Who Shook the Kop'. Had serious injury not robbed him of one of his greatest assets, he would surely have ranked even higher.

To read more from Paul Tomkins, click here to visit The Tomkins Times>>

To purchase the eBook 'Best XI Liverpool', visit Amazon here>>