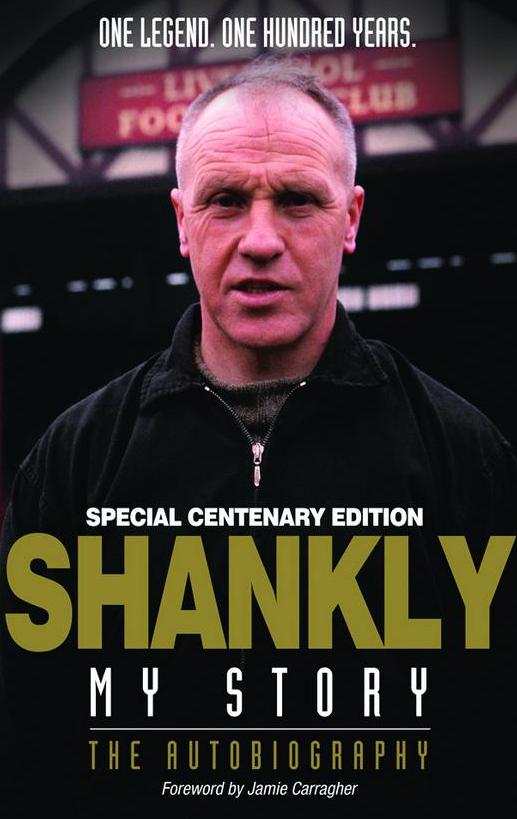

Free: Shankly in his own words

A special centenary edition of 'Shankly: My Story', Bill Shankly's only official autobiography, has been re-released to coincide with the 100th anniversary of the legendary manager's birth.

The hardback, which includes a fascinating foreword by former Liverpool defender Jamie Carragher, sold out on its original release in 1976 and again four years ago.

'Shankly: My Story' tells the Scot's journey in his own words, providing in-depth analysis of his revolutionary work at Anfield and explaining his incredible relationship with the club's fans.

Supporters can order their copy now by clicking here, while Liverpoolfc.com today has an exclusive extract from the book for fans to enjoy below.

I was born in a little coal-mining village called Glenbuck, about a mile from the Ayrshire-Lanarkshire border, where the Ayrshire road was white and the Lanarkshire road was red shingle. We were not far from the racecourses at Ayr, Lanark, Hamilton Park and Bogside.

Ours was like many other mining villages in Scotland in 1913. By the time I was born the population had decreased to seven hundred, perhaps less. People would move to other villages, four or five miles away, where the mines were possibly better.

I had four brothers, Alec, or 'Sandy' as we called him, Jimmy, John and Bob, and five sisters, Netta, Elizabeth, Isobel, Barbara and Jean. I was the youngest boy and the second youngest in the family. All the boys became professional footballers and once, when we were all at our peaks, we could have beaten any five brothers in the world.

At first the family lived in a two-apartment house. Then, as we grew, we got the house next door and knocked a hole through the adjoining wall to make four apartments. Sometimes we slept six in a room, with hole-in-the-wall beds and, below them, camp-beds that pulled out.

Everyone in the village knew everyone else and the doors were ever open. My mother's key was in the outside of the front door morning, noon and night, so you could have walked into our house anytime you wanted to. You could walk into anyone's house and say, 'Good Morning, Mrs Smith', or 'Mrs Davidson' or 'Mrs Brown'.

My mother's name was Barbara - Barbara Gray Blyth before she married. Her brother Robert played for Rangers and Portsmouth, where he became chairman, and her other brother, William, played for Preston and Carlisle, where he became a director. My mother was my greatest inspiration.

First and foremost, she brought up ten children and they were all born at home, which I think is a miracle. To bring up such a large a family in our circumstances must have been a terribly hard job for her. She never had very much, but what she had she was willing to share with anybody else. She had no enemies. I have never heard anybody say anything against her.

She was always calm, never lost her temper and was so loyal to her family. Latterly, only my brother John and my mother were left at home. John was working at a pit some distance away, and he did not get home until eleven o'clock at night. He was always working on the afternoon shift and I remember how my mother used to watch for the lights of the bus coming over the hill, bringing John home. Then she would get his supper ready.

In the end she lived for my brother John, who had an unfortunate life, including a lot of heart trouble, and who was the only one of us who did not get married.

John was the middle brother and the smallest, at five feet six inches. He went to Portsmouth as a teenager and I think the training must have been a bit too much for him. He went to Luton from there and was leading goal-scorer. Then he suffered from an overstrained heart muscle. He played for a long time afterwards, but was never the same.

He went back home and played for Alloa and then went back to the pit. My mother was a month off being eighty when she died, not long after she had fallen downstairs. I was manager of Huddersfield Town when she passed away. I received the news by telephone, and I cried. Suddenly I felt a long way from home.

John died just after the Real Madrid-Eintracht European Cup final at Hampden Park in 1960. He had a heart attack in the stand and was taken from the ground to the Victoria Hospital, Glasgow, during the match, and died that night.

Though my mother was proud of her family, she did not boast and always had time for others. She used to visit relatives in a place called Douglas, where my father was born, seven miles away in Lanarkshire. Maybe five or six of us would go with her and walk to Douglas and back. She would think nothing of that. And she would give away her last penny or her last stitch of clothing.

She used to go to Glasgow on the train to see her sister and her sister would come from Glasgow to our village and perhaps see a coat or something belonging to one of the kids. It was maybe too small for them or too big for them and she would say, "Look at this, Barbara", and my mother would say to my aunt, "Take it, you can have it." She would give anything away.

I don't think people returned the compliment because I remember I once fancied a bike belonging to my cousin at Yoker. It was a lady's bike. I learnt to ride it and was desperate to get it so my mother paid a pound for it and three shillings and sixpence to bring it home on the train. She couldn't afford it, but she paid for the bike because I wanted it. And they'd had lots of stuff from her.

My father, John, was a postman for a part of his life, but for as long as I could remember him he was a high-class tailor of handmade suits. Tailoring was in his blood. All my relatives and all my sisters could make dresses and alter skirts. I can remember them sewing and darning everything. My father also used to do small jobs in the village, altering clothes for people. If you could alter clothes you could make a bigger living out of that than out of making clothes.

Sometimes when he had done a job for someone in the village the person would ask, "How much is it?" "Two shillings," my father would say. "Oh, I've only got a shilling, Johnny," they would say.

"Oh, it's all right," he would say. "Pay it some other time." And he would never bother about it. I don't know what his wages would have been, but he did not keep much for himself. He didn't smoke or drink. The only thing he did for relaxation was go to the pictures. He loved the pictures.

He used to walk four miles there and four miles back. There was never more than two or three wage packets coming into the house at the same time and my father used to work on clothes for the family, changing long pants into short pants and making dresses for the girls.

He was a fighting man. Not in the sense that he would go looking for trouble. No. But he was spirited. If you had said anything critical about Scotland or his family he would probably have killed you! You would sometimes get the impression that he was a militant man. But he was dead honest, a straightforward man who had no time for fools or practical jokers.

My father did not play football, except at a juvenile level, but he was an athlete, a quarter-miler. He only ran locally, but he was hard to catch - even in his older days. He never lost the skill. There were four years between all the boys, and the order of the family was boy-girl, boy-girl, and so on.

Alec, my eldest brother, was twenty years older than me. He played for Ayr United before the First World War. Then he was in the Royal Scottish Fusiliers. After the war he was troubled by sciatica and went back to the pits. Eventually he finished and was not working at all. Alec was a lean man, about five feet nine inches tall.

Jimmy, who was four years younger than Alec, could have been one of the finest centre-forwards ever born. Sheffield United bought him from Carlisle United for £1,000, which was a big fee then.

He was five feet eleven, thirteen-and-a-half stone and as strong as a bull, but was possibly a victim of circumstances. Jimmy was good in the air and could belt the ball with both feet, but there were a lot of great players then. The teams were full of them. Sheffield United had players like Jimmy Dunne, Freddie Tunstall and Billy Gillespie.

So Jimmy went to Southend United for six seasons and was leading goal-scorer for six seasons. He played his best football in the Third Division (South). He was a big help to the family. Southend paid him eight pounds in the winter and six pounds in the summer and his money helped to keep us all. He helped us during the winter, too.

Jimmy's last season was at Barrow, where he played with a bad heel. His league goal-scoring record of thirty-nine in a season still holds at Barrow. Jimmy's last season was my first season at Preston, in 1933. He went back home with his wife from Yorkshire, who later became a schoolteacher, and we helped him to buy a wagon and start a coal business because he had helped us so much.

Bob, four years younger than John, whom I have already written about, played for Falkirk for seventeen years and then became manager of Falkirk and Dundee. Our careers ran parallel. I played for Preston when Bob played for Falkirk. He took Dundee into the European Cup in 1962 and they scored eight goals against Cologne. Dundee had a tremendous team, with players like Ian Ure, Alan Gilzean and Jimmy Gabriel. Bob later became manager of Hibernian and then general manager and director of Stirling Albion.

Bob was about five feet ten inches and looked the most like me. He is a quiet type, but that does not mean that he is not interested. Bob is a genuine fellow, a one hundred per cent man.

If the whole world was like my family, there would be no trouble, and I am not just being kind to my folks when I make that statement. Times were hard when I was a boy and we were hungry, especially in the wintertime. There were farms all around us and we used to steal the potatoes and turnips and cabbages and everything. The village policeman had an awful job. We used to know his every movement. We had spies. The farmers were watching for us, but there was a lot of territory to cover and, when it was getting dark at night, it was hard for them to see!

A chap used to come in with his big wagon from Strathaven, a beautiful village near Hamilton. He sold loaves, scones, cakes, currantcakes - they were brilliant, the currant-cakes - biscuits, milk, all sorts of things. And we used to take things from his wagon.

One night we took a whole bunch of bananas from the wagon of a fruiterer from Clydeside - the biggest bunch you could ever imagine. It took four or five of us to carry it and the bananas lasted for weeks. Other times we would go to the pits and help ourselves to a bag of local coal from the hundreds of tons that were there.

We knew we were doing wrong, but did not think of it as stealing really. It was devilment more than badness. When we had nothing and took something we did not call it stealing. We were hungry. We needed to satisfy our appetites.

Our parents were too proud even to think we were poor and they would never imagine their children had been pilfering.

"Oh, no, not our Jimmy!" If we had owed a millionaire a penny we would have been told, "Pay him!" But there is a moral in all this, because when we grew up we realised that some of the things we had done as boys were wrong, but we had learned from mistakes and possibly that made us better people in the long run. If you go through life doing more good than bad, that should tip the scales in your favour.

My father was a man of character and he disciplined us. We were frightened of him of course. Some boys today are not frightened of their fathers and that's a bad job.

Once, when I had misbehaved at school, one of the teachers, Mr Kirkwood, said, "Do you want your punishment from me or your father?" "From you," I told him. That is the kind of respect I had for my father. Everyone should respect their father. Later in life you can use the lessons you learned as a youngster to help you deal with the young. I had a code to live up to as an athlete. I had to be fit and behave myself. And when I became manager I had a code of discipline for the footballers. But I didn't put anybody in jail or fine them. I had my way of doing things and it was mainly based on mutual respect.