Tomkins: Age of transfer success

In his latest article for Liverpoolfc.com, columnist Paul Tomkins provides an in-depth look at the best – and worst – value-for-money transfers in the Barclays Premier League era.

The notion that players aged between 20 and 22 make the ideal signings has gathered weight in recent times. Anyone younger may just be a flash in the pan, while older players tend to command bigger wages (because they're used to being paid well) and have a diminishing sell-on value.

In June, with this in mind, I thought it would be a good time to look back at Liverpool's Premier League signings - over 100 deals - to see how closely value for money related to age. Before I go any further, I'd like to point out that there are always exceptions to any given rule, and that it's up to the individuals involved in such decisions to weigh the pros and cons and make a decision.

We can all think of great young buys and rubbish older purchases, just as we can all think of rubbish young buys and great older purchases. But what's the general trend? Does the theory about buying players aged between 20 and 22 hold true?

My starting point was Graeme Riley's incredible Transfer Price Index database, and also some of the work I'd done filtering the results in 2010 for the book we co-authored (along with Gary Fulcher), "Pay As You Play: The True Price of Success in the Premier League Era".

First of all, for a basic overview, I split the transfers into five age groups: under 20, 20-22, 23-26, 27-28 and 29 and over. In the under 20s, I excluded the really young signings made for the youth team who never went on to start a league game (all clubs make loads of these types of signings, and precious few pay off; however, the ones that do tend to make it all worthwhile).

Due to the study spanning the entire Premier League period, TPI inflation simply had to be used; comparing fees from 1993, 2002 and 2011 are pointless without taking inflation into account, and it should be clear to anyone that football inflation is radically different to 'everyday' inflation - although it is calculated in a similar way. Instead of working out the value of a basket of shopping, our inflation method measures the changing price of footballers.

(TPI inflation is calculated by finding the average transfer fee in any given season. For example, the average transfer fee in 2004-05 was £2m; in more recent times it's been £5m. So a £20m player in 2004 would have cost ten times the annual average; a £20m player in 2009 would have only been four times the average. When this is converted into a "current day purchase price" (CTPP), the £20m paid 2004 becomes £50m in 2009.)

The reason we came up with the Transfer Price Index system was to compare purchasing across eras. In 2009, £5m was the average fee paid. A mere 15 years earlier, it was the record fee paid. The average price of a transfer in 1992-93 was roughly £500,000. It was 10 times that amount within 16 years. These are all within the "Premier League era".

The point of all this is that whereas Paul Stewart, for example, cost £2.3m in 1992, his CTPP works out at £15.3m. Djibril Cissé and Emile Heskey, both at prices circa £33m, cost only a fraction less than Andy Carroll.

When all prices are converted to CTPP, be they from 1992 or 2011, they can be viewed on the same terms (and as such, all fees quoted herein are CTPP). This paints a picture of the financial side; but how do you objectively assess how good the players actually were in the red of Liverpool?

One clear sign of success as a transfer is the player starting a large number league games. As the database records every league start, these can be looked at as markers of achievement; bad players don't play a lot of games for a club like Liverpool. It doesn't mean that someone who makes 200 appearances is brilliant - sometimes steady Eddies provide that type of value. (Example: John Arne Riise.)

It's only fair to say that some of the age groups have only a handful of players, which makes the sample size small. The numbers, for qualifying transfers up to 2011, were as follows: nine U20s; 23 20-22s; 41 23-26s; 16 aged 27 and 28; and 15 aged 29 or over.

The age group that makes the highest number of starts, on average during the players' time at Liverpool FC, is the fabled 20-22 range, at 63.4. The 23-26 group follows closely thereafter, at 59.7, and a little way behind them come the 27/28 year olds, on 45.3. Then there's a big drop to the 29+ group - who obviously have a short shelf life anyway - at 20.3.

As if to prove that players below 20 can be very hit and miss (and indeed, more miss than hit in Liverpool's case), the 16-19 range only made 16.7 starts on average.

On average, the 29+ age group were the cheapest, at £2.3m, just behind the teenagers, at £3m. But none of the other three groups average out below £8m; proving that players in their 20s obviously cost a lot more money.

The most expensive group is the one aged 20-22 - prime targets - but despite costing on average roughly £3m more than the 23-26 and 27-28 groups, they perform better than both when it comes to limiting CTPP loss. In other words, they provide a sell-on value that more than makes up for the high initial fee. Xabi Alonso cost £24m in today's money, played five seasons for the club, then was sold for £38.6m, as a 27-year-old.

(Due to inflation, it's actually very hard to make a CTPP profit; if you buy at £5m, but sell at £8m - a profit it normal terms - you have made a CTPP loss if the average fee at the time of sale has risen to £10m; and football inflation almost always rises. Therefore, while individual deals make CTPP profits - Fernando Torres, as the most successful Liverpool example - the averages of all five groups result in a CTPP loss; but it's the nature of that loss that is telling. All members of the TPI project accept that clubs work differently in terms of accounting, and the amortization of players' values, but this is designed as an indication of performance in relation to the original transfer fee. We also accept that free transfers - which might be costly on big wages - can skew the results a little, but these still comprise a small percentage of overall trading.)

In terms of Liverpool's Premier League dealings, the CTPP loss for the teenagers is just £92,843. For the 29+ bracket, it's only £1.7m, given that relatively small fees tend to be paid to start with. Mid-ranked of the five groups is '20-22', at £3.7m. The second worst group is the 23-26, at an average £4.3m loss per deal. But the worst - and, for me, the moral of this entire story - are the 27- and 28-year olds, at £4.6m. As I noted in Pay As You Play, the average fee for a footballer drops sharply after the age of 28; clubs can sense a 30-something looming.

Occasionally it might make sense - United won titles thanks to the contributions of Dwight Yorke and Dimitar Berbatov (despite losing fortunes in sell-on value) - but the law of averages warns against it. After all, when Chelsea bought the imperious Andrei Shevchenko for what amounts to over £60m in today's money, at the age of 30, who thought he would perform so badly?

How Good?

The one subjective measure I included as an additional "bit of fun" (but hopefully with some value in the result), was a rating for all of the players out of 10, based on how well I thought they had done in a red shirt. I tried not to be too heavily swayed by the price-tag, but also took it into account to some degree.

It was only when I took the averages for each age range that some interesting results leapt out: yet again, 20-22 was the star bracket (containing the likes of Reina, Agger, Lucas, Alonso), with a mark out of 10 of 7.0; well above the overall average mark of 6.1. It's one thing having a healthy sell-on value, but on the whole, players of this age played well. (Of course, the likes of Diao and Cissé proved costly mistakes.)

[Since this piece was originally written for my website, Joe Allen has arrived aged 22, and looked every inch a star.]

Next came the 23-26 year olds - buoyed by the inclusion of Torres, Hyypia and Hamann, but weighed down by Diomede, Dundee, Josemi and Cheyrou - with 6.2; slightly above average overall, but unremarkable. The worst two categories were the extremes: over 29s and under 20s, at 5.4 and 5.6 respectively. With teenagers you don't always know what you're getting, and with over 29s a decline is often already in motion.

That leaves one category. Dead-on average, at 6.1, were the 27-28 year olds.

Transfer Price Index Coefficient v.2.0

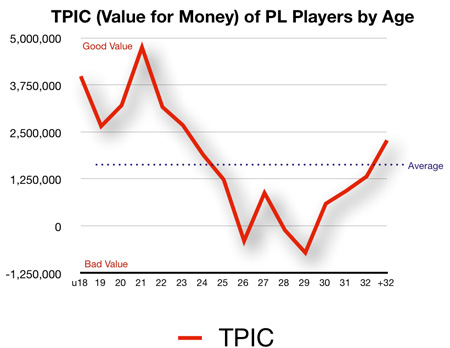

Last year, as an addition to this overall project, I created TPIC - the Transfer Price Index Coefficient. The aim was to judge the best and worst transfers during the Premier League era (not that football began then, but because our data only stretched that far), based on the number of games played, the fee paid, the fee recouped and the number of games started.

For TPIC, free transfers were excluded, and the date-range was limited to 1994-2011. So the data used is a little different to that used in the first section of this article. On top of that, in a further filtering of results, I created a version removing all players still at their respective clubs, given that their data following the move is not definitive (with games still to be played, and/or transfer fees to be recouped). That left around 1,500 deals.

To create a simple coefficient, I decided to multiply the number of games played by 100,000, to bring the number into the millions, so that the CTPP loss or profit - also likely to be in the millions - could be brought onto a similar level, for addition or subtraction. This seemed like a neat way of doing things.

(It was only then that it occurred to me that for Pay As You Play I'd calculated the average cost - in relation to transfer fee - of a Premier League start. It worked out at £54,541 per selection in the XI. However, when applying TPI inflation, the 2010 figure was virtually £100,000. As the average of every game started is £100,000, then each start gets rewarded with £100,000.)

So, the new coefficient was basically the average number of games started by each age group, multiplied by 100,000, plus (or minus) the CTPP profit (or loss). The higher the remaining number, the better value the age group. With the data set so much larger than that of just Liverpool, a more accurate picture should emerge; but on top of that, it provides something to compare the Reds' business against.

To start with I'll look at all ages - 16 subsets, with only those under 19 and also those over 32 grouped together. After this I'll cluster them into just five bands - the ones used at the start of this piece.

As you can see, 21 is the best-value age, and 29 is the worst. For some reason 26 is worse than 27, but otherwise there's a clear downward trend between 21 and 29, and then a rise in value for money at 30+. The ages of 25 to 32 remain below the overall average, but nominal fees paid for those aged over 32 can often result in a couple of worthwhile seasons; although obviously this is the one area where goalkeepers are only entering their peak years, and doubtless skew the figures somewhat (paying fees for outfield players aged 33 or higher is practically unheard of).

Best Players

The best Premier League signing according to my TPIC calculations is Cristiano Ronaldo. He was signed aged 18, for £31.5m in today's money, but started a healthy 157 games before being sold for £102.8m CTPP. Nicolas Anelka ranks second, with a purchase fee of just £1.7m and, after 50 starts, a sale figure of £68.7m. Indeed, Arsenal fill spaces two-to-five, with Anelka, Overmars, Vieira and Toure. The average age of the top ten is just 21.

Liverpool's top-ranking TPIC transfer is Fernando Torres, who made the club a £22m CTPP profit after 91 starts. Next is Xabi Alonso, at 19th overall, followed by Sami Hyypia, in 26th.

The worst TPIC transfer is the aforementioned Shevchenko, who only started 30 games after what still remains the biggest TPI fee (in terms of Premier League purchasing), and left for free. Liverpool's worst transfer in these terms remains Djibril Cissé, who cost £33m CTPP, and left for just £8.7m after a mere 29 starts; leading to him ranking 14th from the bottom across almost 1,500 deals. Emile Heskey's purchase and sale CTPPs are almost identical to Cissé's, but he started 118 games; even so, he's still in the bottom 40. Both were the perfect age; they just weren't quite the perfect talent.

Conclusion

And so, as noted earlier, there will always be exceptions to any given rule.

One of Liverpool's best signings of the past 20 years - Gary McAllister - was 35 when he signed. But he's the only definite success out of 16 singings aged 29 or over. Add the eight signings aged 28-29, to make a pool of 24 incoming players between 1994 and 2011, and the outright success tally still resided at just one, and even then, he's remembered for a golden two months.