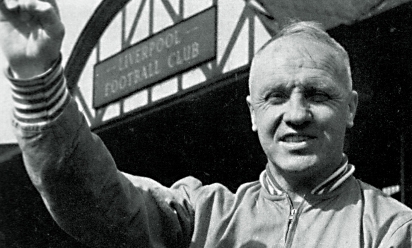

'I painted a portrait of Shankly'

The author of an intense 700-page novel on the life of legendary Liverpool manager Bill Shankly has explained why he wrote the story with a view to creating an 'experience' for the reader.

David Peace, a writer based in Tokyo who has previously used Brian Clough as a source for his unique brand of fiction, released 'Red or Dead' last month.

He then visited the LFC TV studios for an exclusive interview, explaining the inspiration behind choosing Shankly as his latest subject and the reasons for his much-discussed repetition.

Why choose Bill Shankly as the subject of your latest novel?

My previous books are rather different. They are much darker books - about the Yorkshire Ripper; the miners' strike; the worst 44 days that Brian Clough had in his career, at Elland Road. I was a bit sick of these dark tales and I wanted to write something about a good man and also a story that was inspiring to people now. Sometimes people accuse me of being over the top but I don't think you could find a better man to write about than Bill Shankly.

It was just a desire to tell the story of what he did for Liverpool Football Club from 1959 to 1974 - the incredible rise that built the foundations of the modern club. And then also the second half, what happened after the resignation, which to me was a bit of a mystery I suppose. My footballing memories really begin in 1974; the first match I ever went to was the one when Brian Clough brought the Leeds team to Huddersfield Town. My footballing memories really begin with Bill Shankly resigning. I suppose it's different for people who live on Merseyside or have supported the club, but in those days there wasn't quite the coverage of football.

For me growing up, I heard the stories about Bill Shankly but he wasn't the presence. I know he was on Merseyside because he still had the Radio City show and things like that. To me there was the mystery of why he resigned when he did and what happened to him. I just thought it was a fantastic story. There are moments, of course, after he retired, when I feel he had his regrets and some darker days. But particularly in the first half, this incredible rise, I hope it's inspiring for people who don't just live in Liverpool or support the club. It's just a great story.

You said you wanted to write about a good man; in your research, what did you discover that led you to conclude that Shankly was a good man?

My granddad, my dad and I were Huddersfield Town supporters - sadly, he was the gift we gave to you. He left in 1959 to come here. I grew up with my dad telling stories of what a great man he was and what a great socialist he was. The research took about a year, and then coming over to Liverpool and meeting people; it's easy to say he was a good man, but he really was. It's often the reverse - you look for something behind the image. But this was what it was. It was 24 hours a day, his obsession and devotion to football and specifically Liverpool Football Club. He always thought the best of people, and people reacted to that and he brought out the best of people - whether it was the groundsman, the players or most of all the supporters. That tremendous bond he had with the supporters, to actually comprehend and realise the depth of the emotion between him and the supporters was incredible.

What makes 'Red or Dead' different?

The fact that it is a novel. Some people might take issue with this but, to me, and it can sound a bit pretentious, I was painting a portrait of him rather than taking a photograph. I hope when people read it, even if they disagree or don't think it's exactly right, they think it's true to the spirit of the man. The one thing a novel can do that is a little bit different from a biography is to perhaps let the reader feel the story more emotionally. The first half of the book is a hard read in places because I wanted the reader to appreciate the struggle and sacrifice that he went through. There is a tremendous amount of repetition there, this day in, day out and ceaseless hard work. If it works for the reader I hope it's a kind of living experience - when you get to the end of the first half of the book when Bill Shankly resigns you feel as exhausted and drained as he must have felt, to try to understand why he did the things he did and how he did them.

How did you find the experience of writing the book?

It was completely different from, for example, writing four books about the Yorkshire Ripper. It was a much more uplifting and inspiring experience. It's a measure of the man that when I was over here and talking to people, people were really helpful. Sometimes writers and journalists can be a bit guarded with each other, and a bit possessive. But with Bill Shankly it's completely the opposite, people just want to share things.

How much did you know about Shankly and his time at Liverpool before embarking on the project?

One of the very first games I can remember watching is the famous Liverpool-Newcastle FA Cup final. That's one of the first games I can remember watching on the telly. I knew the dates, as you do as you grow up; in those days you had to learn which team won the FA Cup in which year. I knew these things. But it really never clicked with me that Liverpool had gone so long without winning anything. There was a seven-year period for Shankly after the FA Cup and the league championship, there was a bit of a gap. That was incredible, particularly thinking of modern football. I knew the dates and the cups but there was an element of mystery in trying to find it all out. The first half of the book is very long and goes into this in incredible detail. Not even as a supporter of Liverpool Football Club, but just as a football supporter, I found that detail - the attendances, the weather, the different team-sheets, the results - to be the fabric and texture of football. So it's all in there.

The book is incredibly detailed - what lengths did you go to?

I wanted it to be a lived experience for the reader. There's a big national research library in Tokyo; every morning I went down there, they have got a lot of the British papers. Unfortunately not local papers, but they have got the national papers. I just went through every game of every season that he'd been in charge. There's a lot of that in the book. I became really obsessed with this, going through game after game after game. That was one aspect. At the back of the book I've put all of the books that I used, because mine is a novel. If people want to know more, those books are there for further reading.

There are so many anecdotal stories about Bill Shankly. Does that help a writer or make your job more difficult?

One of the other parts of the research was the messageboards, with the internet and the fansites. There are just so many fantastic stories. This was a man who would let the fans go up to his house any day of the week, and they did every day of the week and knock on his door and go in and have a cup of tea. Or he would meet them on trains, walking around or in cafes. There are so many stories of the way that fans could meet him. It's just fantastic the way he could transform people's lives and make them feel so important. The book is 720 pages, it could easily have been another 720 pages.

What did you feel you learned about Bill Shankly from when you started your research to completing the book?

The absolute level of devotion and love he had for football and specifically this club. You hear it, but to actually kind of live it was quite a revelation to me. It wasn't something he just turned on and went for a press conference or in the programme notes. From the minute he woke up to the minute he went to bed, he was thinking about Liverpool Football Club and the supporters of Liverpool Football Club. He had no other interests really. I found it inspiring and also very humbling really.

'Red or Dead' is far more than just a football book: what do we learn about life and politics through following Bill Shankly's life in Liverpool?

It would be impossible and wrong to write a book about Bill Shankly that didn't also incorporate the socialism that informed his life. He described it as something he was born with. He was a great admirer of Robert Burns, his favourite book was a biography of Robert Burns and he saw Robert Burns as an early socialist. He famously said Jesus Christ was the first socialist. Socialism, to him, really mattered. It informed the way he then worked with the groundsmen, with the famous boot room staff, with the players and with the supporters. He didn't differentiate; everybody was part of the club, it was this whole community and everybody was equal.

There's a famous scene in the book, but it's also a true story, when after they had been promoted from the Second Division they had a reception. The chairman said: 'To Bill Shankly, the greatest manager the world has ever seen'. Shankly jumped up and said: 'It's not about me, it's about a team, we're a team of workers.' I suppose that's one of the contradictions of the book - I don't think he would have wanted a 720-page book about him. I don't think it is really; it's more about this man, this club and this city. He never saw himself as special or unique. He was, in many ways, an ordinary man, who just did these extraordinary things.

You have a unique style of writing - that constant use of repetition as a device, was that something you had used before?

I've used it before but probably not quite to the extent I've used it now. If people are interested in the book, I would urge them to have a good look at it before they buy it. I don't want people to be disappointed or annoyed by it. You would have to have a good read of it in the book shop first. It was a style that, I think, suited particularly the first half. The style of the book was inspired by something Shankly said himself - after he retired, he said football was like a river, it was relentless, it went on and on and on, and there was no stepping out of it. I thought it was a fantastic image and it is, even as a supporter; we're at the start of a new season, we're going to go for it all again, it's another season and all the games again. There is this repetition. It can be very draining and exhausting for us as supporters so you can't believe what it would be like for managers now and a man like Shankly, who was so obsessed. I wanted to try to capture this constant repetition, day in, day out. There are some very long scenes repeatedly of the training. But I felt that if you say 'Bill Shankly trained every day with the team for 15 years' and leave it at that, it doesn't capture what that actually means. I was trying to get a style that allowed the reader to try to feel what it was like to be in this river that went on and on.

[SLIDESHOW]

How much licence did you give yourself to make it a work of fiction?

The facts, the attendances and those kinds of details, are very important. To me it is like painting a portrait. I want the book to be true to the spirit of the man. I hope and I don't feel that there's anything in the book that is not true to the spirit of the man. There are some scenes where I am imagining conversations between people, but there also so many hints in interviews and other books that I have tried to bring it all together and kind of dramatise it.

The second half of the book focuses on his life after Liverpool Football Club. What does 'Red or Dead' tell us about the last seven years or so of Bill Shankly's life?

Originally, instinctively, that was going to be all the book was. But when I started to do the research, I thought there was no way you can tell the retirement of a man if you don't tell the story of the work. The work is the first half and then there is the retirement. I'd heard the stories and some people have said Bill Shankly died of a broken heart, and he was a kind of King Lear figure in the wilderness. I think, and it's just my opinion, that is a bit simplistic. He resigned and before he resigned, he said: 'My work is my life, my life is my work'. I don't think, like many of us and like I've seen with my father and my grandfather, they quite understand what retirement will mean without that work. Definitely there were moments when he had great regrets about what he'd done. He must have had very mixed feelings to see the success of the team.

The one thing he really wanted that he never got was the European Cup; then to see the European Cups coming, he must have had very mixed feelings. But I don't think this idea that he died of a broken heart or he felt somehow ostracised from Liverpool Football Club, is the whole story. There could have been no doubt for him about the affection and reverence with which the fans held him. After the resignation, there are a few chapters when it does get very dark. But I kind of pulled back because that's when the anecdotes of the fans going up to the house or meeting him on the train or seeing him in cafes, that's when all those stories come in. I did end it with one story that I got from the messageboards. After Paris, the third European Cup, somebody wrote that there had been the big party, the great celebration, but over in the corner just at the bar, neither of them with a drink, were Bob Paisley and Bill Shankly in conversation like the old days. I thought that was the way to end it because I don't think he died like a bitter man or of a broken heart.

How pleased have you been with the initial reaction to the book?

So far it has been overwhelming, particularly from the supporters of Liverpool Football Club. This can sound odd, but I didn't really write the book for the supporters of Liverpool Football Club. Many of my friends support Liverpool and they had always been telling me Shankly stories. I thought it was like coals to Newcastle, people know this. Having said that, I did feel a great responsibility - I wanted to write a book that did justice to the man, that people if they did read it, who supported Liverpool, weren't going to hate. People, particularly in this city and around the club, have been overwhelmingly positive. But I'm under no illusions; it's not to do with me or my writing, it's to do with their love for Bill Shankly.

I've heard it described in some quarters as the bible of LFC. How did that make you feel?

It's almost overwhelming. I did feel as I was writing it that it was increasingly the gospel of Bill. This rise, taking Liverpool from the wilderness, there is something biblical about it. To me, it's almost the story of a saint - a modern-day saint. I hope it's an inspiration. Always at the back of my mind, I'm thinking of my own kids. I hope that particularly young kids read the book, if they have got the patience to read it these days, and might find that this is an inspiring story, a different kind of story. If you struggle and you work, you can do things and change things.

'The Damned United' was made into a film... do you envisage the same for 'Red or Dead' and who would play Bill Shankly?

There's a man, who is well known to some Liverpool Football Club supporters, called Mike Jefferies - who produced the 'Goal' films and is a lifelong Red. It was really from a conversation with Mike about his great desire to make a film about Bill Shankly and he'd like me to do the script. I said I would be very interested in doing that but I'm a novelist, so before I got to a script I'd have to write a novel. Two years later, I got back in touch with him and sent him the novel - he really loves the novel, which is fantastic. We do really hope it will be a film. I felt a tremendous responsibility writing it so you'd have to be a brave man to play Bill Shankly. But there are people.

What would Bill Shankly make of the modern game?

This is in the latter stages of the book, even in 1979 and 1980 there is a thing he did in the Liverpool Post with the headline 'We must get back to sanity'. He's already railing against the salaries and the wages, and this is 1979. There's a great quote where he says: 'There are people with two cars, swimming pools and big houses - and they have never won a medal.' There's no getting around the fact he would have been appalled at the money and some of the extravagance and so forth that goes on. But I do think, all that aside, he loved football so passionately that he would have loved to watch Jamie Carragher or Steven Gerrard. He would have loved every minute of watching them play. That would have sustained him. The money has always been there in football, it's just that the amounts have increased. Football is still football, it's still about watching men kick a football around. He would have just loved seeing players like that play.

Can you imagine what Bill Shankly might have said to you about the book?

He was such a humble man; I think he would have been embarrassed. But there's quite a lot of Robert Burns in there. He loved that biography of Robert Burns so I just hope he would feel that maybe some of the supporters would love this book in the same way and it would be an inspiration to them. But I wouldn't dare to presume what he would think of it.