Bravery, glory and heartbreak: The story of Bob Paisley's playing career

There were several different incarnations of Bob Paisley in his near-half-century of service at Liverpool Football Club.

Paisley the all-conquering manager of the 1970s and 1980s in his jazzy ties, pinstripe shirts and Lieutenant Columbo-style beige mackintosh.

Paisley the first-team coach of the 1960s, almost always stood or sat immediately to Bill Shankly’s right in his club-issue red tracksuit.

Paisley the pioneering physio of the 1950s and 1960s, clad in his white lab coat as he hooked players up to the infamous EMS (‘electronic muscle stimulation’) machine.

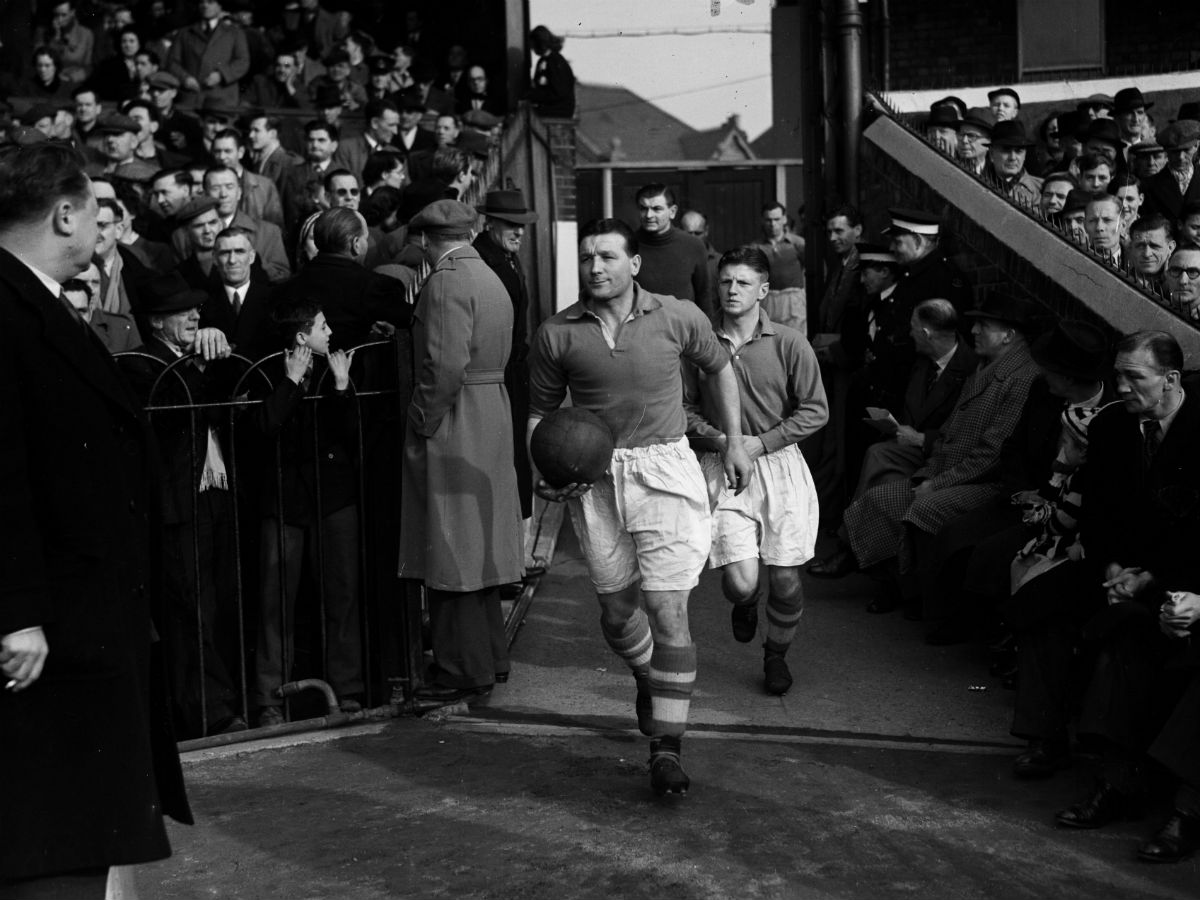

Of all his various guises the one that has perhaps faded from the collective memory most is the one encapsulated by a photograph taken in 1952 and seen below.

In it, Paisley strides authoritatively onto the pitch ball in hand, his head held high and his chest puffed out, his blood-red shirt open at the neck, rolled up at the elbows and tucked into his roughspun white shorts.

The fact that Paisley’s contribution as a Liverpool player has become something of an afterthought is regrettable, but understandable, and mainly down to the passing of time. He was also unfortunate that his 15 years on the Reds’ roster not only coincided with World War II but also with one of the leaner periods in the club’s history.

The resolute defender signed for George Kay’s Liverpool in May 1939 but didn’t make his full competitive debut until 1946 due to his wartime service. He won only one major honour, the 1946-47 league title, and missed the biggest game that took place during those 15 years - the FA Cup final of 1950.

Yet Paisley was admired and respected by fans and contemporaries alike during his playing days, learning lessons that stood him in good stead for the day, two decades later, when he would finally take on the role of manager, and forging strong personal and professional bonds which kept him in Liverpool for the rest of his life despite the strong lure of his native north east.

Anfield was a very different place during Paisley’s playing career, and so was the world of football at large. Young people nowadays can easily ask older relatives or look up YouTube clips if they want to know how Liverpool played during the 1970s or 1980s, but the period during and immediately after the war remains somewhat shrouded in mystery.

Heavy leather footballs, scoreboards operated by hand, goalkeepers in flat caps and wooly jumpers - it might seem romantic and richly evocative now but at its core that era was rough and unglamorous. It was a time when clubs like Blackpool, Bolton Wanderers and Portsmouth all vied for major honours while Liverpool spent eight years in the Second Division; Anfield falling into such disrepair that it lacked even running water before the transformative event that was Shankly’s arrival in 1959.

Flair players such as Blackpool and England’s Stanley Matthews might have managed to distinguish theirselves on the often-bobbly pitches but most pros built their game around hard work and physicality, and ‘Bobby Paisley’ - as the newspapers dubbed him at the time - undoubtedly belonged in the latter category.

Doughty, hardy, diligent, committed - these are the kind of adjectives invariably used to describe him. Even the position he played, variously described as left-half, wing-half or half-back, now feels like a relic of a bygone age, although the consensus seems to be that he was essentially a full-back who played slightly further forward, albeit with more of an emphasis on defence than attack.

“He did get forward, but not in a Trent Alexander-Arnold or Andy Robertson way,” explains journalist and author Ian Herbert, whose Paisley biography 'Quiet Genius' was shortlisted for the 2017 William Hill Sports Book of the Year award.

“A lot of the stuff you read about Bob in match reports touches on stout defending and last-ditch tackles. There was more of a balance between defence and attack in those days, and before he turned up in a very advanced position and scored against Everton in the FA Cup semi-final in 1950 he’d been warned - a bit like Bob would warn Alan Kennedy in later years - not to go up the field too much.”

Naturally, back then techniques, research and knowledge in the field of physiotherapy weren’t as advanced as they are these days - think Bert Trautmann playing on with a broken neck in the 1956 FA Cup final - but even by the standards of the time Paisley was ridiculously, almost recklessly, brave. Press reports tell how he played on while obviously concussed after being knocked unconscious against Newcastle United and stayed on the pitch after having stitches applied to a bad head wound against Derby County.

“I was aggressive but I played the game because I loved and enjoyed it. I might have hurt people and I got hurt myself a few times, but not with any malice. When I went on the field I just wanted to play football,” went his own self-assessment.

Herbert continues: “He seemed to be indefatigable in terms of his spirit and his pain threshold. Perhaps that’s why he was a bit like Shankly in later years in terms of his suspicion of players who were injured. It seems to me that he was the Graeme Souness or Jimmy Case of his day - absolutely unflinching in the tackle.”

Paisley (back row, fourth from right) and Liddell (back row, second from right) line up for Liverpool in March 1947

Off the field Paisley became friends with prolific Scottish inside-forward Billy Liddell, the pair hopping on the number 61 bus each day to travel to Anfield from their club houses on Greystone Road.

“Forgive me if my eyes sparkle when I think of Bill Liddell,” Paisley wrote many years later in his book My 50 Golden Reds. “He would have been a star in any team, in any age. He was often embarrassed when people referred to us as ‘Liddellpool’ during the days of struggle, but I think it was fair enough.”

For his part, Liddell said of his teammate: “He was an honest grafter and a great man to have on your side, tremendously strong and rugged. He never gave up.”

Paisley had moved directly from amateur team Bishop Auckland to First Division Liverpool, and even accounting for the fact that some of the greatest signings in Liverpool’s history have come from far and wide, with the benefit of 80 years’ worth of hindsight it seems a daunting step up for a 20-year-old to take.

“Bishop Auckland were probably the best non-league team in Britain, but it was a huge leap,” states Herbert.

“He probably wasn’t expecting to break into the first team straightaway, but what he had behind him was this sense of having something to prove. Wolverhampton Wanderers and Sunderland [the club Paisley dreamed of playing for in his youth] had both considered him too small, so I think he was very driven to make it. It was just a tragedy that the war broke out. No sooner had he got to the brink of making his debut than war started and everything was put on hold for six years.”

The war was an eye-opening experience for Paisley, to say the least.

Having spent almost his entire life in the small mining village of Hetton-le-Hole, suddenly he was exposed to a myriad of different cultures and climates, all in the most dangerous circumstances imaginable. Serving with the Eighth Army or ‘Desert Rats’, he was present at both El Alamein and the liberation of Rome, riding a tank into the same city where he would celebrate Liverpool’s first European Cup triumph 33 years later.

After the conflict ended Paisley was stationed at Woolwich for three years and only permitted to return to Liverpool on weekends - not that it stopped him making 33 appearances as the Reds won their fifth league title in 1946-47. It was a stunning achievement for Kay’s side in the first full post-war campaign but it was also the beginning of a downward spiral for the club, who would languish in mid-table for the next six seasons before being relegated in 1954. The 1950 FA Cup final offered hope of a glorious interlude but Liverpool lost 2-0 to Arsenal and Paisley was left out of the squad despite fighting back from injury just in time to feature.

“The bottom fell out of my world,” he would tell the Liverpool Echo many years later, but the affinity he had developed by then - not just with the club but with the city and the people who lived there - stopped him going elsewhere.

Says Herbert: “All his life he had that Liverpool suspicion of fancy dans and snobbery. As a manager he only really bought players from England and Scotland, and he particularly loved the Scots because they were such straightforward people. So I think the city played into his world view in some ways, in that there was a real community spirit there. He came to Liverpool for his career but he found friends there, he met his wife Jessie there, and he laid roots down like any working-class lad trying to make their way in the world.”

The end to Paisley’s sadly truncated on-field career came when he was left off the list of retained players for the 1954-55 campaign.

He had made 277 appearances and scored 13 goals for Liverpool but had never been capped by England despite at one point being widely considered one of the best wing-halves in the country. Aged 35, the husband and father had some big decisions to make. The story goes that he considered returning to the north east and resuming work as a bricklayer, the trade he had learnt before his football career took off. Just like that trial at Sunderland and the aftermath of the 1950 Cup final, it was another sliding doors moment when Liverpool could have lost out on the man who would become their most successful manager, but modern-day biographers like Herbert don’t give too much credence to the idea he was truly close to leaving.

Paisley’s unassuming manner makes it easy to imagine him as someone who climbed through the ranks merely by being in the right place at the right times, but a closer look at how he occupied himself for the rest of the 1950s reveals a man utterly determined to make himself an indispensable part of the club’s framework.

Paisley treats the injured Ian St John during Liverpool's 3-0 win over Manchester United at Anfield in April 1964

Having already completed a correspondence course to become a qualified physiotherapist and masseur before hanging up his boots, Paisley sought and was granted permission to visit Liverpool’s hospitals and learn about how injuries were treated after club director TV Williams and Littlewoods founder John Moores intervened on his behalf. Williams, who would later become the Liverpool chairman that appointed Shankly, clearly saw something in Paisley and also entrusted him with leadership of Liverpool Reserves, a decision vindicated when the club’s second string won their first Central League title in 1957.

And Paisley did return to bricklaying - not in the north east, but at Anfield, where he built new dugouts, plumbed in toilets in the Kemlyn Road stand and devised new scoreboards.

“The most difficult time of Bob’s life was when the team was starting to fail in the mid-1950s and he was starting to slip out of the team,” Herbert concludes. “How was he going to provide for his wife and children? Ultimately Bob’s story is one that’s slightly misunderstood because he was quiet, he didn’t project himself in the way we’re accustomed to now. But the determination with which he set about getting his physiotherapy degree and becoming one of football’s early medical men is instructive.

“At that stage there weren’t a lot of coaching roles around, the idea of a backroom team wasn’t really there, but Bob was scrupulous in finding an angle to stay in Liverpool. It was obviously a place that he loved.”

That love would be reciprocated many times over by the red side of the city during the glittering years of 1974-83 and endures to this day.

But it was those darker days in the 1940s and 1950s that made Bob Paisley the man he was.